Rock carving facts

The rock carvings in Tanum are images that were chiselled into the rock during the Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron Age, from 1,700 to 300 BCE. The term “carving” is actually misleading. The images were hammered into the rock using pounding stones, and the tools are sometimes found during archaeological excavations near the sites. The carvings rarely depict everyday life; instead, the images seem to be related to power, ritual, and warrior ideals.

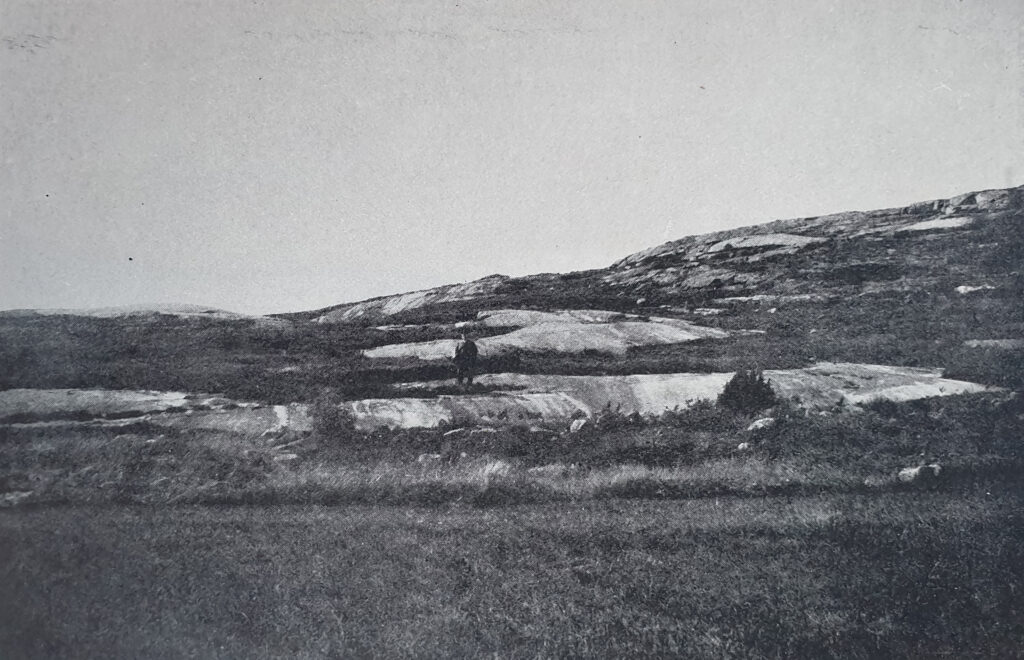

In the Tanum World Heritage area, there are over 600 known sites with rock carvings. Today, these sites are located a few kilometres inland, but when the carvings were made, many of them were situated directly adjacent to the ancient coastline. Due to post-glacial rebound, these panels are now situated between 9 and 17 meters above sea level. Other rock carvings are located at higher elevations and have never had direct contact with the seashore. An example is Fossum, which is situated at an elevation of over 40 meters above sea level. Ships are a common motif on panels, regardless of whether they were close to the Bronze Age sea or not. Therefore, the maritime connection does not necessarily have a geographic basis; rather, the presence of ships reflects the importance of water travel in many parts of Bronze Age society and culture.

What do the rock carvings depict?

Although there are tens of thousands of individual rock carvings, the motifs are relatively few. The most common are the round pits called cup marks, and other recurring images include ships, humans, and animals. Less common motifs include foot soles, circles, wagons, trees, ards (predecessor to the plow), hands, net figures, and weapons. The challenge with rock carvings usually lies not in identifying what they depict but in understanding why the carver made the image. We may never fully comprehend the rock carvings, but by studying the chosen motifs, we can learn a great deal about the world of the Bronze Age people.

Learn more about the rock carvings motifs.

How do we determine the age of the rock carvings?

There are several ways to determine the age of rock carvings. The most common method is to compare images with actual archaeological finds and examine ship depictions engraved on objects from the Bronze Age. The age of objects can be determined through methods such as artifact chronologies or radiocarbon dating (C14 dating). The assumption is that if the depiction and the object appear similar, they are likely from the same era.

There are a few sites where the landscape’s post-glacial rebound can be used to determine the age of the carvings. For example, there is a theory that the carvings at the lower part of the Gerum panel cannot be from the beginning of the Bronze Age because that section of the panel would have been underwater at the time.

When rock carvings overlap each other, it is sometimes possible to determine which image was carved first. By studying these overlapping carvings, called overcuts, it is possible to create a relative chronology. This chronology does not provide the exact age of the carvings but indicates the sequence in which they were made.

Many rock carvings were created over a long period, and images located just a few centimetres apart can have several hundred years between them. Therefore, it is impossible to interpret an entire panel as a single narrative. However, it is sometimes possible to see that multiple images are connected, such as the bridal couple at Vitlycke or the horseback battle at Litsleby. Some panels have a consistent style and execution across most of the images, suggesting that the carvings were created over a relatively short period. An example in the World Heritage area is the Fossum panel, where all the boats look the same, and the people seem to be cast from the same mould.

When were the rock carvings discovered?

The first mention of a rock carving from the Tanum World Heritage area is in 1751 when Colonel Klinkowström wrote: “In Tanum parish, not far from the sea, I have also seen a rock surface with a carved man holding a spear. The story goes that a Scottish leader was killed during ancient warfare and the position in which he was found was carved into the rock.” This refers to the so-called Spear God on the Litsleby panel.

Systematic studies of the rock carvings began in the 19th century when archaeology emerged as a scientific discipline. Carl Georg Brunius, who was a pastor’s son from Tanum, made drawings of several of the large panels in the area between 1815 and 1818. In 1845, the antiquarian and clergyman Axel Emanuel Holmberg visited Tanum and made drawings, including those of the Vitlycke panel. Throughout the 20th century, repeated surveys have led to a significant increase in the number of known rock carvings. In 1969, there were 1,200 known carvings in the entire Bohuslän region, and twenty years later, the number had grown to 2,300. As of 2023, a search for rock carvings in Bohuslän in the Swedish National Heritage Board’s Cultural Environment Register yields nearly 4,200 results.

It is, however, more challenging to determine how long the rock carvings have been known among the local population or whether they were ever forgotten. Many examples exist of residential houses located near or on top of deeply carved and distinct rock carvings, making it difficult to believe that the images went unnoticed. Moreover, the cup marks, also known as “elven mills,” played a role in folklore well into the 20th century. There is, therefore, much evidence to suggest that the images carved into the rocks have been known for much longer than when they were first recognized by scholars.

Are there more rock carvings to discover?

When the large panels were documented in the 19th century, the landscape in Bohuslän looked different. There was almost no forest, and many panels that are now buried were exposed. Therefore, the conditions for discovering rock carvings were better than they are today, and it is likely that the largest panels have already been found. However, there are undoubtedly smaller carvings yet to be discovered, as evidenced by the fact that many “new” sites are exposed each year.

Are the rock carvings visible?

Rock carvings can be challenging to see—many are very shallow and have also been damaged by weathering in many cases. To enhance the visibility for visitors, about ten of the over 600 sites in the World Heritage Site have been coloured in. The colour found on some of the accessible panels is not from the Bronze Age but serves to show visitors what the rock carvings look like. The colour is not an attempt to reconstruct how the carvings appeared when they were made and used, as no traces of ancient paint in the carvings have been found.

Learn more about why some carvings are painted.

One tip for easier viewing of unpainted carvings is to visit the sites in the dark and shine a flashlight on them from the side. The shadows in the carvings make the images much clearer. Depending on how the panel is positioned in the landscape, a similar effect can be achieved in the morning or afternoon. The images are also more visible when the rock surface is wet, such as after rain.