Rock carving motifs

There are tens of thousands of individual rock carving images, but the motifs are quite limited. Those who have visited several rock carving sites quickly start to recognize them. Most carvings depict ships, humans, and animals. However, the cup mark, which is the most common motif, is quite difficult to understand what it might represent.

The descriptions below are general and explain the most common interpretations of the different motifs found in the South Scandinavian rock carving tradition. These images can be seen in Denmark, southern Sweden, and southern and western Norway. The images primarily revolve around people, their objects, and their world. In northern Scandinavia, the rock carvings and rock paintings depict different subjects, with wild animals dominating, such as fish, moose, and bears.

There are also similarities between Scandinavian rock carvings and rock art in other parts of the world. Cup marks exist on all inhabited continents. Ships similar to those in Bohuslän can be found in Spain and Egypt, and images of warriors on horseback and wagons resemble those in Valcamonica, northern Italy. Objects depicted on the Bohuslän rock surfaces, such as swords and shields, have been found in archaeological contexts in other parts of Europe.

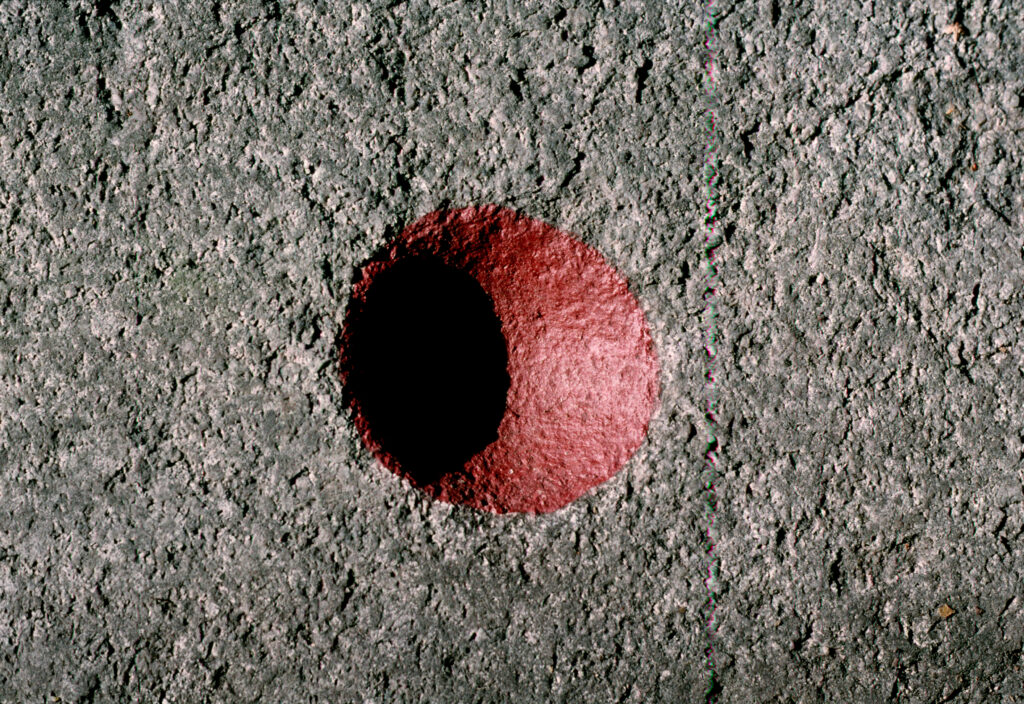

The small dot, the cup mark, is the most common rock carving motif. Some are scattered seemingly randomly on the sites, while others form geometric patterns like rows or circles or are part of other images such as human figures or ships. There are numerous interpretations of cup marks, and their meaning likely depends on the context in which they appear.

The cup mark is also the carving that has been used the longest. Cup marks are engraved on the ceilings of megalithic tombs from the Late Stone Age, and in folklore during historical times, they were called “elven mills” and were used for offerings to ancestors by greasing the cups with fat or placing metal objects in them.

Ships are the most common images that actually represent something easily recognizable. Maritime activities played an important role in the Bronze Age society. All bronze had to be imported, and the mines where copper and tin ores were extracted were located far from Bohuslän – in Cyprus, the Iberian Peninsula, the Alps, and the British Isles. Bronze was important as a symbol of power, weapons, and tools. Bronze objects are found as grave offerings and as offerings thrown into wetlands, demonstrating the significance of the metal. Therefore, the ship carvings can be seen as illustrations or stories about these important and long-distance journeys. The ships may also have a symbolic meaning as the vessels that carry the dead to the realm of the dead, a common belief in many cultures.

The human figures are often armed with swords, spears, axes, and bows. Many have distinctive features such as large calves or noses, helmets with horns, wings, or ponytails. There are many depictions of men, who are phallic and therefore easily recognizable as men. However, women are virtually absent. People with ponytails are usually interpreted as women, but this figure type is very rare. The most common depiction of humans is the small lines that symbolize the crew on the ships, known as crew lines.

There are both domesticated and wild animals on the rock surfaces: horses, bulls, dogs, deer, snakes, and birds. The animals can represent everyday life, such as draught or riding animals, or symbols of life, death, rebirth, power, and the connection between gods and humans.

Footprints are depicted both as bare imprints with toes or as shoe soles. They are often oriented so that the individual standing there faces the viewer of the rock carving. Feet are depicted both in pairs and individually.

Circular figures can be interpreted as wheels, shields, or symbols of the sun, depending on the context in which they appear. Circles on wagons become wheels, and warriors use circles as shields. Freestanding circles are often interpreted as a solar symbol, a motif commonly found throughout Europe during this period.

Wagons appear with both two and four wheels. The latter are interpreted as transportation vehicles, while the former is called war chariots and can be seen as expressions of the ambitions of the ruling elite. However, it is unlikely that chariots were used in the hilly landscape of Bohuslän. The presence of chariots on the panels is more likely due to influences from other parts of the world. The wagons are sometimes depicted with draft animals, with four-wheeled ones being pulled by oxen and two-wheeled ones by horses. Details such as reins are also included in the composition.

There are a few trees depicted. The forests in the Bronze Age were dominated by deciduous trees such as oak, lime, ash, and hazel. The stylized trees are difficult to identify as specific species, but they resemble spruces more than deciduous trees. Perhaps spruce was depicted precisely because it was rare in nature. It also stands out in a landscape where there are almost only deciduous trees, as it remains green throughout the year.

There are uncommon motifs such as weapons, detached hands and legs without accompanying humans, net figures, and labyrinths. Other images can be clear but still difficult to decipher. Many things that were common and important during the Bronze Age are not depicted on the panels. The clearest example is the absence of houses, crops, and everyday objects like hoes, shovels, baskets, and pots. Their absence is also an important clue to the function of the images and how they can be interpreted.